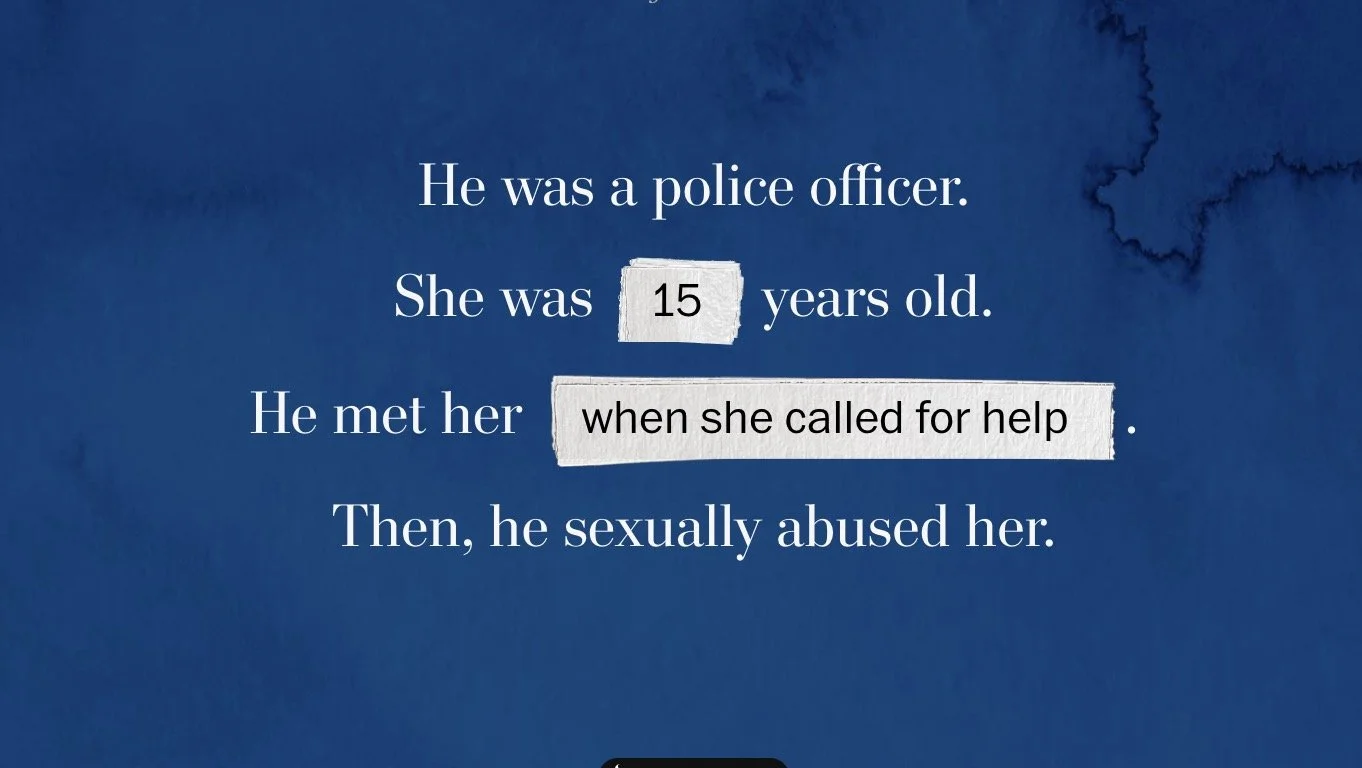

Hundreds of law enforcement officers have been accused of sexually abusing children over the past two decades, a Post investigation found

This was the first story in a six-part series I pitched that uncovered how police departments have failed to take basic steps to stop predatory cops from using their positions to exploit children. I spent months earning the trust of the girl and her family, while obtaining records that revealed the highest-ranking police leader was texted about potential sexual abuse of a minor by an officer with a troubled past. Five days later, that officer locked a 15-year-old girl in his truck and sexually assaulted her. My reporting led a federal judge to halt a trial in the case and a jury to order the city of New Orleans to pay $1 million to the victim.

At least 1,800 officers were charged with crimes involving child sexual abuse from 2005 through 2022. Nearly 40 percent of convicted officers avoided prison time, a Post investigation found.

When I set out to quantify how often law enforcement officers were being arrested for crimes involving child sexual abuse, I never expected to end up with a number so high. Predatory cops often used the power of their badges to find and silence their victims, while officials at every level of the criminal justice system failed to protect children and punish abusers.

I led a team of Post journalists to examine prosecutors’ failures to hold officers accountable; the lack of supervision and rules for School Resource Officers; what happens when predatory officers go to trial; the lasting impact on communities; and how the Trump administration is handling these cases. The series had immense impact, changing the course of cases across the country and prompting the Justice Department to issue new guidelines for the nation's 20,000 school police officers, a groundbreaking effort to protect students.

An Internet mob wanted to rescue a 13-year-old girl. Instead, they terrified her, derailed real trafficking investigations and incited ‘save the children’ violence.

“Don’t know if this is true, but can’t hurt to spread the word.” This is the common misconception many people have when they encounter warnings about sex trafficking online. To show the actual harm caused by one conspiracy, I tracked down its origins, talked to the people who spread it and followed its ripple effects to Homeland Security, the National Trafficking Hotline, the Jan. 6, 2021 attack on the U.S. Capitol, and most importantly, the lives of real teens caught up in the lies. This story prompted more than 3,700 people to sign up for The Washington Post. You can read more about my reporting on Neiman Storyboard.

Other stories about the institutions failing to prevent and respond to the sex trafficking of American children:

I embedded with the Las Vegas Vice Unit on multiple overnights to show how the city was still sending trafficked teens to juvenile detention.

Through jail interviews, court documents and police records, I told the story of Chrystul Kizer, whose case tested whether child sex trafficking victims charged with murder should be treated differently. My reporting was referenced by the Wisconsin Supreme Court, which ruled in Kizer’s favor.

Along with many news stories, I’ve followed vigilante “predator catchers,” a teen trafficking victim charged as a trafficker and Ohio’s long battle against a girl from my hometown.

A cash-strapped rancher, a virus-stricken meatpacker, an underpaid chef, a hungry engineer: The journey of a single burger during a pandemic

I love to take issues that seem entrenched or stale and tell stories that make you think about them in a different way. During the pandemic, I wrote about shortages and supply chains by following the journeys of three single items: an N95 mask, a container of Clorox wipes and a takeout cheeseburger.

In between those stories, I regularly anchored our coverage of the 2020 protests in D.C., including the day federal officers fired rubber bullets and chemical gas at protestors outside the White House.

How did he get this way? And what was going on in his brain? But also: why was he cleaning carpets for a living?

With 4 million pageviews and counting, Vaughn Smith’s story is my most viral piece of journalism. A friend of Vaughn’s mentioned him to another reporter, who talked to an editor, who talked to my editor, who talked to me. I was deeply skeptical. The more time I spent with Vaughn, the more I realized that this story was about far more than his astounding and very real abilities. So off we went to MIT to get our brains scanned together. I often have the opportunity to work closely with our audio producers to tell stories for our podcast audience; this one is one of the best.

Other stories I have loved and learned from

After more than 11 years at The Washington Post, it’s hard to pick favorites. Whether it takes two hours, two days, two weeks, two months or two years, each story is possible because of a team of hardworking people who care about telling the truth and getting things right. Most importantly, these stories exist because of the sources who say yes — to sending documents, to sharing their expertise, or to letting this curious girl from Ohio come hang out. If there’s a story you think should be told, please write to me at mjessicacontrera@gmail.com.